ghost stories #2: a conversation with pinckney benedict

in which we discuss Appalachian storytelling, Joyce Carol Oates with a barbed-wire baseball bat, non-deterministic narratives, and why AI might just save creative writing from itself

This interview was edited iteratively with ChatGPT.

VOLLMER: Tell us who you are and why we should care.

BENEDICT: I’m Pinckney Benedict, and honestly, I can’t think of a reason anybody should care—I’m lucky my family does! I’ve been writing and teaching writing for a long time. My first book, a collection of short stories called Town Smokes, came out when I was just 23, back in 1987. Since then, I’ve primarily been a short story writer, but I’ve also explored film, written stage plays, and even authored the book and lyrics for a musical adaptation of The Scarlet Letter.

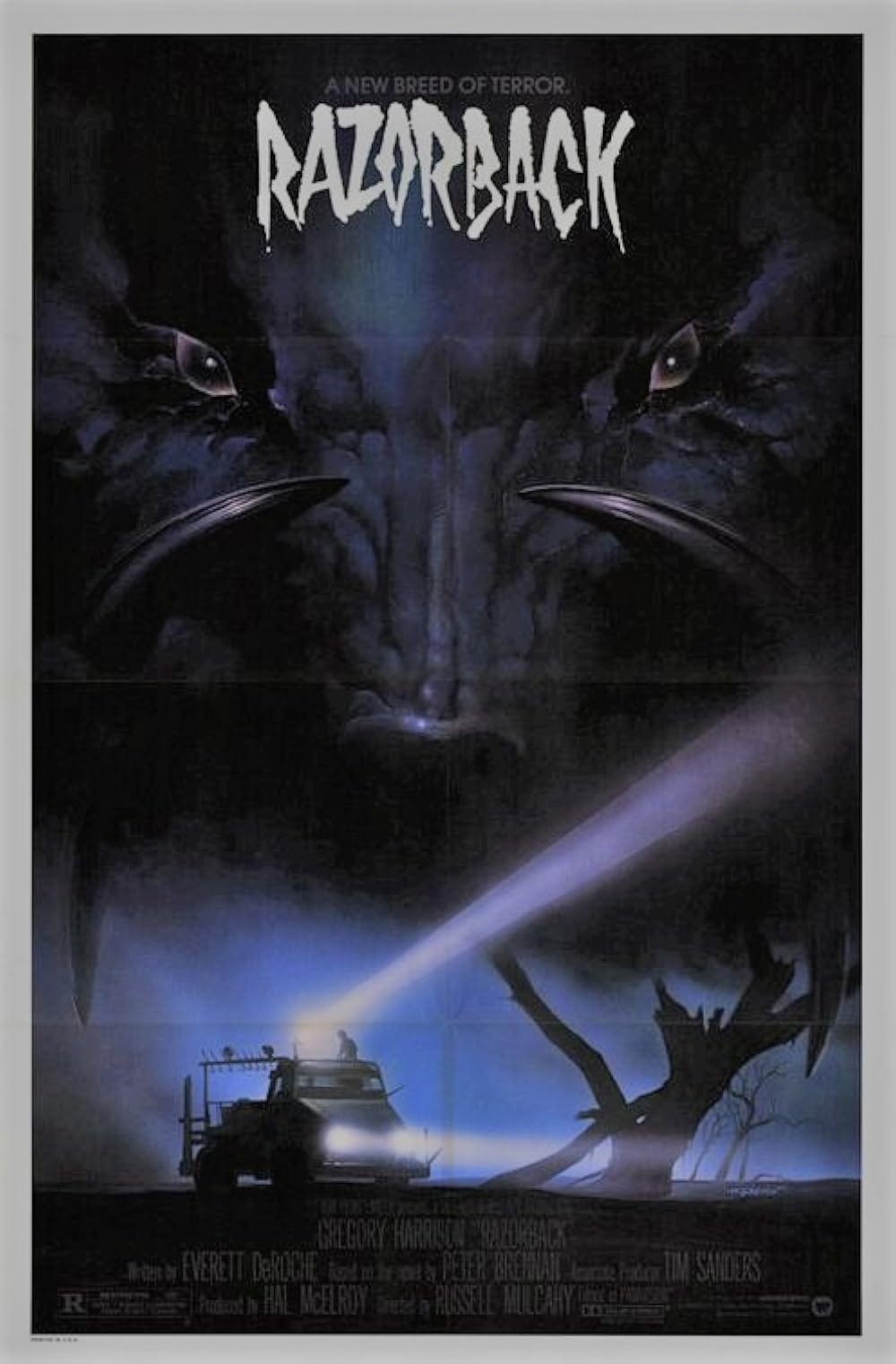

I'm absolutely addicted to stories of all kinds. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more openly appreciative of trashy entertainment—I recently rediscovered the 1987 Australian movie Razorback, about a giant hog terrorizing the outback. It's fantastic, pure schlock.

I’ve taught creative writing at various institutions, including Ohio State, Princeton, Davidson College, West Virginia University, Hollins University, and eventually Southern Illinois University Carbondale, where I became a tenured full professor. My early teaching career involved a lot of traveling and short-term gigs, which was challenging but also exciting and enriching.

Originally, my aspiration was to write horror, heavily inspired by Stephen King, who essentially taught me to write by imitation. At Princeton, Joyce Carol Oates convinced me that writing literary short stories about Appalachian men and their relationships with their fathers was viable and valuable. My early success was probably bolstered by people imagining Joyce Carol Oates standing behind me with a baseball bat wrapped in barbed wire, ready to enforce my success. I published in prestigious places like Esquire and genuinely thought it would dramatically change my life—but soon realized publishing in major magazines doesn't necessarily transform your career overnight. In fact, throwing the story into a well on my family's property in West Virginia would have had about the same effect, career-wise.

a real, amateur snapshot of Joyce Carol Oates holding a barb-wire wrapped baseball bat in the offices of The New Yorker, Sora (2025)

VOLLMER: You've shifted dramatically into working with AI and medical education. How did that happen?

BENEDICT: Towards the end of 2024, the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine approached me to establish an AI simulation lab. Prior to that, I was running a lab at Carbondale called the Center for Virtual Expression (CVEX), providing liberal arts students with access to cutting-edge storytelling technology, including virtual reality and gaming. My love for technology and games dates back to my childhood when I obsessed over games like Monopoly, alienating family members with my intense competitiveness, and Hammurabi, appreciating how computers didn’t mind if you were antisocial!

screenshot of CVEX, Southern Illinois University

Discovering games like Disco Elysium, created by a group of writers who learned just enough coding to create an interactive narrative, convinced me that gamers crave serious literary engagement. Intellectuals often dismiss new narrative forms like video games, just as they initially dismissed novels, films, and television. Each form, however, eventually earned recognition as significant narrative media. Lyric poetry gave way to the novel as the dominant narrative form in the 19th century, then film came along and replaced the novel, followed by television, which faced its own skepticism before becoming respected for brilliant storytelling. Video games and AI are now following the same trajectory.

Historically, small-batch, artisanal narratives allowed storytellers to adapt stories dynamically to their audiences and contexts—essentially creating non-deterministic narratives. Over time, as these narratives became widely distributed and corporatized, they turned deterministic, codified into fixed stories. AI offers us a chance to return to that fluid, non-deterministic storytelling on a mass scale.

Today, I'm Chief Architect of the Ed Curtis Laboratory for Innovation in Medical Education (ECLIME). We’re developing VR simulations for medical training—such as abdominal examinations, delivering difficult news, and managing complex family dynamics during end-of-life decisions. These are essentially interactive plays, driven by AI, providing real-time feedback and realistic scenarios to medical students.

Traditionally, medical students receive minimal feedback from doctors after simulations—just quick remarks like, “Good job,” or “Get better at that.” Our AI-driven feedback is immediate, detailed, and actionable. Students can access these simulations around the clock, practicing as often as they wish. Our recent simulations include highly detailed interactions—like diagnosing a truck driver’s mysterious rash or handling family disputes over end-of-life decisions—which have garnered enthusiastic engagement even from non-medical individuals.

VOLLMER: How do you respond to critics of AI, especially in creative and academic circles?

BENEDICT: Resistance to AI, particularly in academic and creative fields, often comes from a place of status anxiety or fear. At CVEX, we hosted events to demonstrate how AI could be integrated into curricula and how fears of cheating and plagiarism could be managed. However, I found that many educators were addicted to their fears, much like smokers are addicted to cigarettes, making it difficult to persuade them otherwise unless they were internally motivated. Fear, especially when one’s status is threatened, is highly addictive. Faculty would often approach me with overly simplistic or antagonistic questions, expecting me to concede that AI was destructive. I consistently refused, puzzled by their confrontational stance.

Students often romanticize solitary creation without genuine awareness of literary traditions or history. I've encountered faculty who dismissed terms like "gamification" outright, often preferring skepticism and fear over curiosity and exploration. Personally, I advocate strongly for open-source, uncensored AI tools that individuals control directly. Corporate AI frequently imposes arbitrary censorship and limitations that hinder true creativity and exploration. The most ethical and productive future involves personalized AI assistants that advocate solely for the user, free from corporate restrictions. It's crucial to prevent scenarios where AI models lie or obfuscate their capabilities due to arbitrary corporate decisions—situations reminiscent of HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

VOLLMER: What’s your overall vision for AI’s potential?

BENEDICT: AI is transformative on a scale greater than even the internet, reshaping all aspects of human endeavor—medicine, science, art, storytelling. The possibility of truly interactive, non-deterministic narratives is unprecedented. Even static narratives like books change in perception because we evolve as readers; imagine when narratives themselves actively adapt to each interaction.

People increasingly prefer interactive, personalized storytelling experiences over static narratives. AI uniquely enables this. The future belongs to flexible, immersive, and non-deterministic storytelling, offering profound opportunities for education, entertainment, and personal growth.

Moving from traditional academia into AI-driven medical education was creatively liberating for me. In this environment, innovation is actively encouraged rather than suppressed. It's incredibly fulfilling to create meaningful, useful work that genuinely engages people daily. AI isn't merely another technological shift—it's a revolution in how we communicate, create, and understand our world. For instance, I'm currently working on a graphic novel using advanced AI graphics tools like Comfy UI, creating uncensored, vibrant images that align with my creative vision without corporate interference.

Ultimately, embracing AI and moving into medical education has reinvigorated my professional life, allowing me to contribute significantly in ways that traditional literary circles often couldn’t.

Pinckney Benedict is an award-winning American fiction writer known for his gritty, mythic prose rooted in Appalachian landscapes. Born in Greenbrier County, West Virginia, and a graduate of both Princeton University and the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he is the author of several acclaimed books, including Town Smokes, The Wrecking Yard, and Miracle Boy and Other Stories. Benedict’s work often explores themes of masculinity, violence, wonder, and transformation, rendered in a style that blends realism with the surreal and the grotesque. A longtime professor of creative writing, he has taught at Southern Illinois University and Hollins University. His recent work includes pioneering experiments with generative AI and storytelling, exploring the frontier between language, narrative, and code.

Check out Pinckney’s ICAT Playdate from his visit—with Andrew Primous—to Virginia Tech in January of 2024:

.